Living Fuzzballs: The Life Cycle of Wooly Apple Aphids - Kesler Science Weekly Phenomenon and Graph

Folks in the Northeast have been noticing something a little odd. Fine strands of fiber seem to be clumping in the crevices of apple trees. Is this some kind of mold or fungus? Is it a bird's half-hearted attempt at making a nest?

Believe it or not, these mini-cotton balls are insects! Aphids, to be exact. Apple trees that appear to have white pom-poms glued to their bark have an infestation by the aptly-named woolly apple aphid. To be sure, these aren't your typical bugs.

Tmaq97, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Tmaq97, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Why are woolly apple aphids, well, woolly? They produce these fine, waxy filaments from glands in their abdomen. The fibers disguise their appearance and taste horrible, helping to deter predators. In fact, the wool is so useful that some of their predators, like the harvester caterpillar, cover themselves in the wool of the aphids they eat!

The wool keeps the aphids safe in another way too, because insecticides are less effective; the fuzzy exterior keeps the chemicals from soaking in.

Woolly apple aphids also have a really interesting life cycle. For one thing, they used to migrate back and forth between elm trees and apple trees. Now that elms are in short supply, they mostly stay on apple trees.

They start as eggs or nymphs that have been dormant in the apple tree roots all winter. They grow into wingless females in the spring who climb up the trunk to feed on leaves and clone themselves asexually for two generations. Another weird thing - these females don't lay eggs when cloning - they give "live birth!"

When the third generation is cloned, they show up with wings! They fly to a second tree to eat and clone more female offspring.

When fall is approaching, they fly back to the original tree, where they start producing wingless male AND female offspring. Those offspring now switch to sexual reproduction with two parents to produce the next generation of eggs. 😱

Are the apple trees destroyed by these furry invaders? Not often! The aphids poke through the bark with their mouth parts to access sap, but this only causes mild harm to the host plants.

One issue that can be a problem: woolly aphids also produce a thick, sticky substance called "honeydew" as they feed on the sap. Honeydew deposits encourage mold growth, which isn't great for trees.

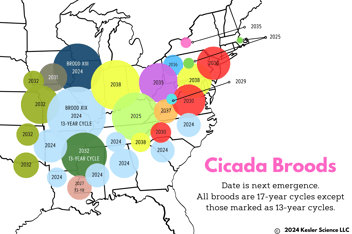

Researching the strange life cycle of the woolly apple aphids got me thinking about different reproduction types in the animal kingdom. Aphids aren't the only organism that switches between asexual and sexual reproduction.

Asexual reproduction that creates only females is great for growing a population quickly because every single offspring can grow more offspring; in a population that is half females and half males, only 50% of the organisms can bear more offspring. Why don't species just stick with asexual reproduction?

It's a good short-term strategy, but there are drawbacks to endlessly cloning yourself. Check out the graph below to see why:

If I shared this graph with my students, I might use the following questions to get them thinking deeper:

💡 What happens to the number of mutations over time?

💡 Why does sexual reproduction produce healthier populations over time according to the graph?

💡 Based on the data in the graph, why would asexual reproduction be a good short-term strategy for the woolly aphids?

💡 Tricky bonus question: any idea why there is a frilled lizard and a certain famous movie monster on the graph?

I hope you and your class have a "woolly" great conversation about this one! 😉

- Chris

.png?width=352&name=Spookier%20Extinction%20Graph(1).png)