That's quite a bird! - Kesler Science Weekly Phenomenon and Graph

I wouldn't say I'm a serious birder, but I do admire the epic trek that many species take over the Gulf of Mexico during springtime. I live in the middle of a migratory path called the Central Flyway, so lots of enthusiasts come to my neck of the woods in Texas to catch a glimpse of migrating birds like martins and hummingbirds heading towards their summer homes in the central US and Canada.

There's a bird species I stumbled across last week that couldn't be more different than the cute little warblers flying over my home. If I saw this bird in my neighborhood, I'd keep my small pets inside! I'm talking about the shoebill, a monster bird that lives in East Africa.

The shoebill stork's scientific name, Balaeniceps rex, means "whale-headed king." Makes sense - these birds can tower up to 5 feet tall and sport a massive bill. It's the third largest bill among birds!

With their huge, sharp bills, these birds are expert predators. They stand motionless in East African swamps for hours, then suddenly strike and gulp up catfish, snakes, or young crocodiles with their massive beaks. Crocodiles!

This imposing creature is actually pretty tame around people, though, and is a favorite among birders who visit Africa. They use their bills for other purposes too; they carry cool water to sprinkle over their nests when it gets too warm.

Unfortunately, shoebill populations have been dropping due to habitat disturbance, hunting, and people who try to capture them as pets. There are only around 5,000 birds left in the wild. This has landed the birds at "vulnerable" status, which means they are at risk of extinction. In contrast, there are about 35 million ruby-throated hummingbirds in North America!

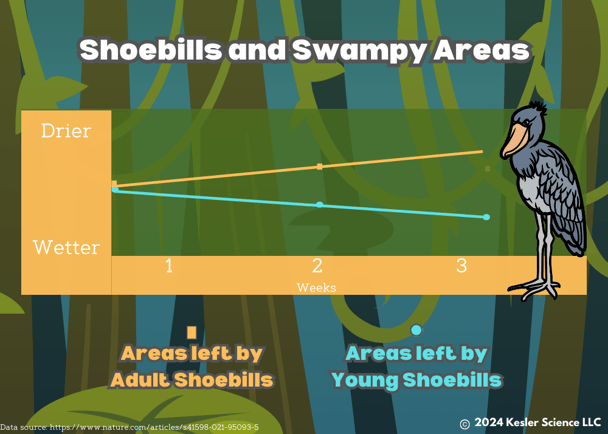

Scientists are concerned, so ecologists have been collecting data on shoebill movement in the swampy areas they call home. They found something interesting - shoebills tend to move around in their habitats, but not all shoebills move away from the same areas. It depends on age! Can your students figure out the trend?

Both adult and young shoebills start out in the same level of wetness in their swampy homes, but adult shoebills leave areas that are becoming drier, while young shoebills leave areas that are becoming wetter.

Can your students think up any reasons that younger, smaller shoebills would prefer drier areas, while adult shoebills prefer wetter areas? Can they think about changes in water flow and droughts - how would those events possibly affect shoebills?

Hope you'll enjoy wading into this topic! 😉

- Chris

By the way, if I brought this graph to my classroom, here are some questions I would ask my students:

💡In the graph above, how many weeks did scientists conduct their investigation about shoebills?

💡At the end of the experiment, were there more young shoebills or older shoebills in the wetter areas? Why do you predict this is?

💡If a shoebill habitat started flooding more often, how would this negatively impact the population?

*photo credit to frank wouters from antwerpen, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

.png?width=352&name=crickets%20and%20cows(1).png)